I’m excited to share my full take on one of the most persistent nutrition myths we’ve carried for decades: that eggs are harmful for your heart because of cholesterol. The truth is, the latest science shows a very different picture. For most people, eggs are not only safe, but they can be one of the most nutrient-dense, health-promoting foods you can eat to support both heart and metabolic health. In this post, I’ll walk you through the evidence, the lab markers I personally track, and the practical steps I recommend to maximize their benefits while minimizing any risks. My goal is simple: to show you why eggs deserve a regular place in your diet, and how to use them as a powerful tool for long-term vitality.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Why this matters to your health

- What’s inside an egg: the nutrient reality

- How the fear of cholesterol began: Ancel Keys and the low-fat movement

- What cholesterol actually is and why you need it

- Meta-analyses and guideline changes: eggs are not a cardiovascular enemy

- What matters most for heart disease: a two-factor model

- Breakfast matters: eggs vs oats and orange juice

- Trans fats and processed vegetable-based “butters” — the fats to avoid

- Glucose spikes harm arteries — the case for glucose management

- Blood tests that actually predict heart risk — what I monitor

- How many eggs should you eat — and is 10 eggs per day really fine?

- Protein context: eggs and daily protein goals

- Supplements I use and recommend — exact dosages and rationale

- How I implement eggs, supplements, and testing — a step-by-step protocol I follow

- Practical recipes and meal ideas — how I eat eggs

- Common concerns and myth debunking

- FAQ

- Put it all together: my recommended daily protocol (summary)

- Final thoughts — eggs are not the enemy

Introduction: Why this matters to your health

For decades many of us were told to fear cholesterol and to avoid eggs. That guidance shaped diets, food industry products, public policy, and medical teaching for a generation. But science evolves. When you dig into the evidence, you find that the original studies that triggered the low-fat movement were associative and incomplete. Over time, more rigorous research like randomized trials, meta-analyses, and mechanistic studies changed the picture. The bottom line I will argue and document in this article is this: for most people, dietary cholesterol from eggs does not translate into dangerous blood cholesterol or increased cardiovascular risk, and eating eggs often is a healthful choice.

What’s inside an egg: the nutrient reality

Let’s start with the basic biochemistry. An average large egg has two distinct parts: the yolk and the white. They are nutritionally very different and both valuable.

- Egg yolk: approximately 5 grams of fat and around 185 milligrams of dietary cholesterol, roughly 3 grams of protein, and concentrated fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K), choline, lutein, zeaxanthin, B vitamins, and antioxidants. The yolk is where the micronutrient magic lives.

- Egg white: roughly 90% water and about 4 grams of almost pure protein per large egg, with negligible fat and no cholesterol.

Many people in the 1990s removed yolks and ate only egg-white omelets because they were taught to avoid dietary cholesterol. That certainly solves the dietary cholesterol problem — but it also throws away most of the vitamins, choline, and antioxidants. Choline is especially important: it supports liver function, neurotransmitter synthesis, and cell-membrane integrity. Eggs are one of the best natural sources of choline.

How the fear of cholesterol began: Ancel Keys and the low-fat movement

The modern cholesterol panic traces back to the mid-20th century. Two foundational epidemiological studies shaped public opinion and policy:

- The Seven Countries Study by Ancel Keys, which showed a correlation in a selected group of countries between dietary fat intake and heart disease mortality. The visual graphs made a powerful impression: more fat seemed to equal more heart disease.

- The Framingham Heart Study, which demonstrated that high blood cholesterol, high blood pressure, and smoking were risk factors linked to heart disease.

These results were influential — and not without problems. The Seven Countries Study excluded some nations (France, Germany) where fat consumption was higher but heart disease mortality lower. The studies were also—and most importantly—associative. Correlation does not equal causation. Despite that caveat, the data were compelling enough at the time to inspire public-health directives that recommended limiting dietary cholesterol (the 1977 US dietary guidelines capped cholesterol at 300 milligrams per day) and to launch the decades-long low-fat craze.

The unintended consequences of low-fat guidance

To make low-fat processed foods palatable, the food industry replaced fat with sugar, refined starch, and additives. That shift produced a generation eating low-fat but high-sugar diets — a combination we now know is much more damaging for metabolic health. Rising rates of obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome tracked that shift, and the scientific community revisited prior assumptions.

What cholesterol actually is and why you need it

Cholesterol is an essential molecule in the human body. It is not a toxic waste product we should purge. It’s a structural building block for cell membranes across all tissues, a precursor for steroid hormones (like cortisol, testosterone, estrogen), and a component of myelin that protects neurons. Genetic or developmental conditions that impair cholesterol synthesis produce severe developmental and cognitive problems, which underscores cholesterol’s fundamental biological importance.

One major scientific correction that reframed our thinking is the discovery that the cholesterol we eat is not the main determinant of cholesterol in our blood. The liver manufactures about 80% of circulating cholesterol; only roughly 20% is dietary in origin. Most dietary cholesterol is either not absorbed or is promptly excreted. Importantly, individuals differ in their absorption: some are “hyper-responders” where dietary cholesterol raises LDL modestly, but for most people this effect is small and not associated with worse clinical outcomes.

Meta-analyses and guideline changes: eggs are not a cardiovascular enemy

By the early 2000s researchers began aggregating data and performing rigorous meta-analyses. Several systematic reviews and dose-response analyses confirm there’s no increased CVD risk—or even potential benefit—with up to one egg daily. A major review in 2009 examined dietary cholesterol, blood cholesterol, and cardiovascular outcomes and concluded that dietary cholesterol — especially from eggs — did not significantly affect blood cholesterol or increase cardiovascular risk for most people.

Reflecting the weight of the evidence, the 2015 US Dietary Guidelines removed the previous cholesterol limit. The emphasis shifted to saturated fat and trans fats as dietary components more clearly linked to adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

What matters most for heart disease: a two-factor model

Modern cardiometabolic science points to a two-factor model explaining atherosclerosis and heart disease risk:

- Particle quality — small dense LDL. Not all LDL particles are created equal. Small, dense LDL particles are more atherogenic (more likely to penetrate artery walls and contribute to plaque formation) than large, buoyant LDL.

- Inflammation and oxidation of particles. Oxidized lipids and systemic inflammation are the other half of the equation. Without inflammation and oxidative damage, even elevated cholesterol may be less damaging.

What drives small, dense LDL and oxidation? Metabolic dysfunction — excess sugar and high insulin states — and certain dietary fats (trans fats) are key culprits. In other words, sugar and insulin dysregulation are central drivers of harmful lipid patterns and vascular oxidative stress.

Breakfast matters: eggs vs oats and orange juice

This is one of my favorite practical takeaways. Many people start their day with oatmeal and a glass of orange juice because of the perceived health halo. Oats and fruit juice are carbohydrate-rich and can cause a rapid post-meal glucose spike in many people. Those glucose excursions — especially when repeated daily — promote inflammation and oxidative stress and can lead to the production of small dense LDL particles.

There are controlled studies showing that replacing a carbohydrate-heavy breakfast with eggs reduces markers of inflammation. One trial entitled “One egg a day improves inflammation when compared to an oatmeal-based breakfast without increasing other cardiometabolic risk factors in diabetic patients” showed that diabetic participants who ate eggs instead of oatmeal had reduced inflammation markers without adverse changes in cardiometabolic markers.

So when I say “instead of orange juice and oats, have eggs,” I mean that for starting your day in a way that minimizes glucose spikes and inflammation, eggs are a powerful tool. They’re low in carbohydrates, high in satiety-inducing protein and fat, and rich in micronutrients that support overall health.

Trans fats and processed vegetable-based “butters” — the fats to avoid

Not all fats are equal. The real dietary enemies we should fear are industrial trans fats and partially hydrogenated oils that were introduced as “healthy” replacements for saturated fat in the low-fat era. These fats clearly increase cardiovascular risk and should be avoided.

Examples to avoid:

- Margarines and hydrogenated vegetable oils (especially older formulations).

- Highly processed, shelf-stable “bakery-style” spreads and some plant-based “butters” that contain hydrogenated or interesterified fats.

- Industrial partially hydrogenated ingredients found in some packaged snacks and fast foods.

In short, eat whole-food fats (olive oil, avocado, butter in moderation if you tolerate it) and avoid industrial trans fats and hyper-processed “buttery” spreads.

Glucose spikes harm arteries — the case for glucose management

Even when fasting glucose looks normal, frequent post-meal glucose spikes are harmful. Several studies show that postprandial hyperglycemia contributes to endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress — key early events in vascular disease.

Two studies I reference often are:

- “Postprandial hyperglycemia as an etiological factor in vascular disease” — highlights the direct role of post-meal glucose in vascular injury.

- “Oscillating glucose is more deleterious to endothelial function and oxidative stress than mean glucose in normal and type 2 diabetic patients” — shows that glucose variability itself is particularly damaging.

Reducing post-meal glucose spikes is therefore a primary strategy for protecting arteries and reducing long-term heart disease risk. In practice this means changing meal composition and order (protein and fat before carbs), timing, portion sizes, and sometimes adding targeted supplements that blunt carbohydrate absorption.

Blood tests that actually predict heart risk — what I monitor

Standard total cholesterol is a poor lone predictor. About 50% of people who suffer a heart attack have “normal” total cholesterol. To get a clearer picture I recommend and personally use a more granular panel. These are the tests I usually instruct people to request and how I interpret them:

- Triglyceride-to-HDL ratio — Calculate by dividing triglycerides (mg/dL) by HDL (mg/dL). Target: less than 2. Values over 2 indicate a higher likelihood of small dense LDL and greater heart risk.

- ApoB — A count of all atherogenic lipoprotein particles (LDL, Lp(a), VLDL remnants). Lower is better. It directly reflects particle number; for many clinicians it’s superior to LDL-C.

- High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) — A marker of systemic inflammation. Aim for as close to zero as possible; values <1 mg/L are desirable for low cardiovascular risk.

- HOMA-IR (Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance) — Calculated from fasting insulin and fasting glucose; lower is better. Insulin resistance is a major driver of small dense LDL and metabolic risk.

- Advanced lipid testing — Particle number and size via NMR (e.g., LDL-P, particle size distribution) can reveal if LDL is small and dense versus large and buoyant.

- Cardiac CT calcium score — If you’re middle-aged or older, a coronary artery calcium score is an objective measure of existing atherosclerotic burden. Lower is better. This is not a routine blood test but a critical imaging marker.

How to calculate the triglyceride-to-HDL ratio

Take your triglyceride value in mg/dL and divide it by your HDL in mg/dL. Example: triglycerides 120 mg/dL divided by HDL 60 mg/dL = 2.0. That’s the cutoff I use — under 2 is desirable. If you’re over 2, investigate diet and metabolic drivers and work to lower glucose spikes and insulin.

How many eggs should you eat — and is 10 eggs per day really fine?

Let’s be practical. The title of this piece contains the phrase Why 10 Eggs a Day is Fine because that was the provocative framing used in the original content. What I want to make crystal clear is this: for the majority of people, eating multiple eggs a day is safe and often beneficial. But “fine” depends on your metabolic context and lab results.

Key points I use to personalize egg intake:

- If you have normal lipid particle patterns (low ApoB, low LDL-P, triglyceride-to-HDL < 2), low inflammation (hs-CRP < 1 mg/L), and low insulin resistance (normal HOMA-IR), then several eggs a day are almost always safe and can be metabolically beneficial.

- If you are a “hyper-responder” (your LDL-C and ApoB rise significantly with increased dietary cholesterol), I watch particle number (ApoB/LDL-P) and inflammation closely. Some hyper-responders can still tolerate eggs if other markers remain healthy, but monitoring is essential.

- If you have familial hypercholesterolemia or very high baseline ApoB/LDL-P, then dietary adjustments should be guided by a lipid specialist; eggs may still be part of the diet but quantity and context should be individualized.

So could 10 eggs a day be fine for someone? Yes, it could be safe for a metabolically healthy individual with robust markers — but that is not universally applicable. I personally eat eggs daily, often 3 to 6 a day depending on my protein needs and daily activities. I recommend regular testing, and if you want to eat 10 eggs every day long-term, do the tests I described every 3-6 months until you’re sure your lipids and inflammation remain healthy.

Protein context: eggs and daily protein goals

Eggs are a great source of high-quality protein but each egg has about 6 to 7 grams of protein. If you weigh 70 kilograms (~154 pounds), and you follow a guideline of eating about 1 to 1.5 grams of protein per kilogram for maintenance or higher for muscle building, your daily target may be 70–105 grams of protein. That would equal roughly 10–15 eggs to meet daily protein needs if eggs were your only source — which is why people often say “20 eggs for 150 grams” in a purely mathematical sense. In practice, I use a diversity of protein sources (eggs, dairy, fish, poultry, legumes, and supplemental whey or collagen when necessary).

If you want to use eggs as a primary protein source:

- 3–4 eggs in the morning is an excellent way to start the day with 18–28 grams of protein and stable satiety.

- Spread additional protein across the day from varied sources to meet your total daily requirement.

Supplements I use and recommend — exact dosages and rationale

I want to be explicit here because many readers ask for specifics. I use targeted supplements both to blunt glucose spikes and to support lipid and vascular health. Below are the exact dosages I recommend based on the research and what I personally take. Always speak to your own clinician before starting new supplements.

Anti-Spike style formula (two capsules daily before highest-carb meal)

This category focuses on reducing post-meal glucose excursions. The two molecules I emphasize are:

- Mulberry leaf extract — I recommend a standardized extract providing 250 mg per capsule, standardized to 1–2% 1-deoxynojirimycin (DNJ). Take 2 capsules (500 mg total) 10–15 minutes before your largest carb-containing meal of the day. Rationale: randomized trials and meta-analyses show mulberry leaf extracts reduce post-meal glucose spikes and insulin responses by up to ~30–40% depending on dose and formulation.

- Eryosythrine (lemon-derived molecule) — take 150 mg per capsule, 2 capsules (300 mg total) before the same meal. Rationale: this class of flavonoids can support gut-mediated incretin (GLP-1) release; clinical trials have shown increases in GLP-1 production by around 15–20% after two months of supplementation in some formulations, which helps regulate glucose metabolism.

Dosage summary I personally use: 2 capsules (total 500 mg mulberry leaf extract and 300 mg eryosythrine equivalent) taken 10–15 minutes before my highest-carbohydrate meal. If you purchase a commercial Anti-Spike product, follow the manufacturer dosing; the approach I outlined mirrors common clinical formulations used in trials.

Other supplements I commonly recommend and why

- Omega-3 fish oil — EPA + DHA combined 1,000 to 2,000 mg/day. Rationale: reduces triglycerides, has anti-inflammatory effects, and supports endothelial function. You can find these foundational supplements including CanPrev Vitamin D3 + K2 and high-quality Omega-3 in our VIP Supplement Protocol.

- Vitamin D3 — 1,000 to 4,000 IU/day depending on baseline level. Rationale: supports immune health, endothelial function, and many metabolic pathways. Get your 25(OH)D measured and tailor dose to maintain levels in the 40–60 ng/mL range (consult your clinician).

- Magnesium — 200–400 mg/day of magnesium glycinate or citrate, ideally at night. Rationale: supports glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and sleep.

- Berberine — 500 mg two to three times per day taken with meals for glucose regulation (optional and under clinician supervision). Rationale: berberine has glucose-lowering effects comparable in mechanism to metformin in some studies, but it interacts with medications and isn’t for everyone.

- Coenzyme Q10 — 100–200 mg/day if you are on statin therapy or if mitochondrial support is desired. Rationale: statins can lower CoQ10 and supplementation may reduce myalgias and support energy metabolism.

- Choline — if you don’t get enough from diet (pregnant or lactating women should be guided by clinician) — 250–500 mg/day as choline bitartrate or CDP-choline (citicoline) depending on goals. Rationale: eggs are rich in choline, but if you limit eggs, supplementing can maintain adequate levels.

For more practical tools, recommended supplements, and protocols, explore our full product library.

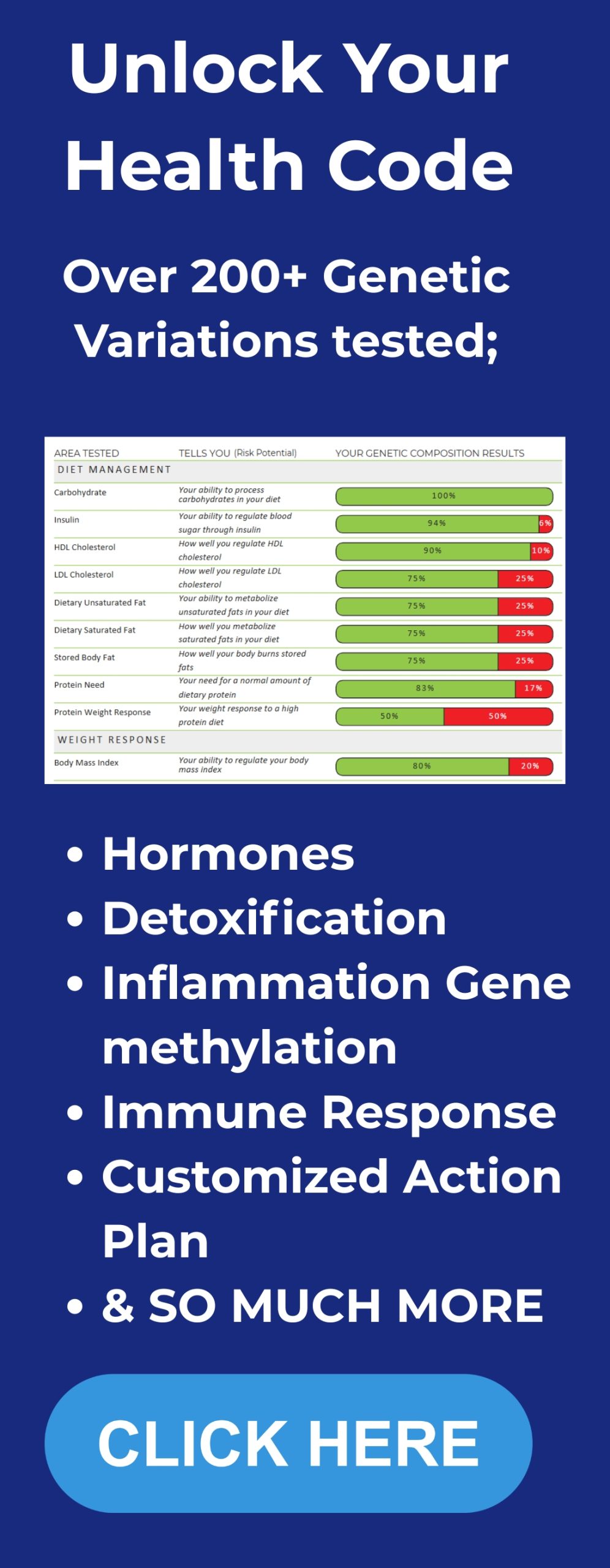

Important safety note: always coordinate supplements with your healthcare provider. If you want to go beyond general guidelines, our DNA Insights Program helps you personalize nutrition, egg intake, and supplement choices to your unique genetic profile. For instance, berberine can interact with certain medications; high-dose omega-3s can affect bleeding risk in susceptible people; and vitamin D dosing should be guided by blood levels.

How I implement eggs, supplements, and testing — a step-by-step protocol I follow

Below is the practical protocol I use with myself and recommend to readers who want to adopt an evidence-based approach to eating eggs frequently while protecting heart and metabolic health. This is a stepwise plan with specific actions, monitoring, and timing.

- Baseline labs: Before major dietary changes or long-term high egg intake, get a baseline set of labs: fasting lipid panel (including triglycerides, HDL, LDL), ApoB, hs-CRP, fasting insulin and glucose (to calculate HOMA-IR), and consider advanced lipid testing (LDL-P) and a coronary calcium score if >45 years old or with family history. Record your baseline. We also provide an Integrative Health Program that combines lab tracking, supplementation, and lifestyle strategies into a clear, step-by-step plan.

- Start with eggs: Replace a carbohydrate-heavy breakfast (oatmeal + juice) with 3–4 whole eggs cooked the way you prefer plus non-starchy vegetables and a small healthy fat source (olive oil, avocado). Eat slowly and observe satiety and energy.

- Introduce anti-spike supplement: If you struggle with mid-morning or post-meal glucose swings, take the anti-spike style supplement (2 capsules containing mulberry leaf extract 250 mg each and eryosythrine 150 mg each) 10–15 minutes before your largest carbohydrate meal of the day.

- Adopt glucose-friendly meal order: Start meals with protein and vegetables, then eat carbs later in the meal if desired. This simple ordering reduces post-meal glucose spikes markedly.

- Avoid trans fats: Remove margarines, hydrogenated oils, and processed “buttery” spreads from your diet and focus on whole-food fats like extra virgin olive oil, avocado, and small amounts of butter or ghee if tolerated.

- Re-test at 8–12 weeks: After consistent changes, retest ApoB, triglycerides, HDL, hs-CRP, and fasting insulin/glucose. Calculate the triglyceride-to-HDL ratio and HOMA-IR. If values remain favorable, continuing higher egg intake is usually safe. If markers worsen (rising ApoB, rising hs-CRP, triglyceride-to-HDL ratio >2), re-evaluate and consider reducing egg quantity and addressing underlying drivers (insulin resistance, weight, refined carbs).

- Ongoing monitoring: Continue checks every 3–6 months if you maintain a very high egg intake (≥6 eggs/day) and especially if you have any family history of early heart disease.

Practical recipes and meal ideas — how I eat eggs

Eggs are versatile. Here are some practical, glucose-friendly ways I recommend preparing them:

- Scrambled eggs with spinach, mushrooms, and a side of avocado

- Poached eggs over roasted vegetables and a small portion of beans (if you want carbs) — eat the eggs first, then the beans

- Omelet filled with smoked salmon and dill (omega-3 boost)

- Soft-boiled eggs with a side salad for lunch

- Hard-boiled eggs as high-protein snacks during the day

Timing tip: if you plan to indulge in a carbohydrate-dense dessert or meal later, take your anti-spike supplement before that meal, and ensure your meal begins with protein and vegetables.

Common concerns and myth debunking

Let me address some common concerns directly:

- Will eating eggs raise my blood cholesterol? For most people, dietary cholesterol has a modest effect on LDL and overall blood cholesterol; the liver adjusts cholesterol synthesis. The minority of “hyper-responders” will experience noticeable LDL increases, but even then, particle number and inflammation are more important predictors of actual risk.

- Are egg yolks “fattening” or unhealthy? No. Yolks provide beneficial fat-soluble vitamins and choline. They increase satiety and can improve the nutrient density of your diet.

- Isn’t saturated fat the main problem? Saturated fat is metabolically neutral for many people but can raise LDL in some — the context matters. Replace trans fats and ultra-processed carbs; focus on overall dietary pattern and metabolic health.

- Are eggs safe for diabetics? Yes, and in some studies diabetic patients who replaced a carbohydrate breakfast with eggs had lower inflammation without worsening cardiometabolic markers. Always individualize under clinical supervision.

FAQ

Q: I have high LDL cholesterol — should I stop eating eggs?

A: Not immediately. First get detailed tests (ApoB, LDL-P, triglyceride-to-HDL, hs-CRP, HOMA-IR). If LDL is high but ApoB/LDL-P and inflammation are low, your LDL may be predominantly large and buoyant which is less atherogenic. Consult a lipidologist if you have persistent high ApoB or a family history of premature cardiovascular disease. Consider a trial reduction in eggs with close monitoring if you’re concerned.

Q: How often should I test my lipid and inflammation markers if I eat eggs daily?

A: If you’re changing diet or trying an aggressive egg strategy (e.g., >5 eggs/day), test at baseline and again at 8–12 weeks. If stable and healthy, go to every 6–12 months. If you have risk factors, test every 3–6 months.

Q: Are farm-fresh or omega-3–enriched eggs better?

A: Eggs from hens fed a diet high in omega-3 produces eggs with modestly higher EPA/DHA and better omega-6/omega-3 ratio. They’re a small nutritional upgrade but not essential if you already take fish oil or eat fatty fish regularly.

Q: What about egg allergies?

A: Egg allergies are common in children and usually present early; they’re handled case-by-case. If you have a confirmed egg allergy, you must avoid eggs and obtain nutrients from alternate sources.

Q: I heard that eating a lot of eggs raises TMAO, a metabolite linked to heart disease — is that a concern?

A: TMAO is generated from some dietary components (e.g., choline, carnitine) by gut microbes. Evidence about TMAO’s role is controversial and dependent on individual gut microbiome. If you’re concerned, monitor global markers (ApoB, hs-CRP) and consider dietary adjustments and probiotics under supervision.

Q: Can I eat eggs if I’m on statin therapy?

A: Usually yes. There’s no need to avoid eggs because of statins. However, discuss with your prescribing physician especially if you take multiple supplements or expect changes in lipid tests.

Put it all together: my recommended daily protocol (summary)

- Breakfast: 3–4 whole eggs cooked with vegetables and healthy fat. No sugary juice or high-glycemic carbs first thing.

- Supplement timing: Take 2 capsules of anti-spike style supplement (total ~500 mg mulberry leaf extract + ~300 mg eryosythrine equivalent) 10–15 minutes before the highest-carb meal.

- Avoid industrial trans fats and hydrogenated spreads; prioritize whole-food fats.

- Daily supplements: omega-3 1,000–2,000 mg EPA+DHA, vitamin D3 1,000–4,000 IU as needed based on blood levels, magnesium 200–400 mg at night. Add berberine only under medical supervision if needed.

- Testing cadence: baseline labs (ApoB, hs-CRP, fasting insulin/glucose, triglycerides, HDL) then retest at 8–12 weeks after the dietary change. Adjust intake and supplements based on results.

Final thoughts — eggs are not the enemy

I want to end with a practical truth: eggs are nature’s multivitamin. They give concentrated, bioavailable nutrients — choline, vitamin D precursors, lutein, zeaxanthin, and high-quality protein — that support brain, liver, and muscular function. When framed in the context of metabolic health, avoiding eggs out of fear of dietary cholesterol is misguided for the majority of people. The biggest dietary risks for heart disease are metabolic dysfunction driven by excess refined carbohydrates and sugars, insulin resistance, and industrial trans fats.

If you want to confidently eat eggs — even many eggs — follow a data-driven protocol: check the right labs, reduce post-meal glucose spikes with meal order and targeted supplements, avoid trans fats, and monitor inflammation and ApoB. That is the practical, science-based path I use, teach, and invite you to try.