Today we’re diving into one of the most controversial topics in nutrition: seed oils. There’s a lot of noise and fear out there, but when you dig into the research, the picture becomes much clearer. While some online voices argue that seed oils are harmful and should be avoided at all costs, the science paints a far more balanced story. In this article, we’ll break down the seed oil debate, explore what the evidence actually says, and share clear, practical recommendations for what to use in the kitchen and how to approach supplements if your goal is to optimize health without overcomplicating your diet. By the end, you’ll know exactly what matters, what doesn’t, and how to make smart, sustainable choices that support long-term wellbeing.

Table of Contents

- Why this matters

- What are seed oils and how are they made

- Key differences between seed oils and animal fats

- What the evidence actually says about health outcomes

- Canola oil versus olive oil: a surprising comparison

- Processing concerns: hexane, heat, and oxidation

- Why context and dietary patterns matter more than the oil itself

- Economic and accessibility considerations

- Practical cooking recommendations

- Supplements and vitamins: clear recommendations and exact dosages

- How I apply this in my kitchen and daily life

- How to choose oils for different uses

- FAQ

- Final thoughts

Why this matters

The seed oil debate has become one of the more heated nutrition fights on social media. People frequently ask me whether seed oils are toxic, whether they cause inflammation, and whether they are worse than butter, lard, or tallow. As with many controversial topics, nuance is the key. Blanket statements like all seed oils are evil or all animal fats are dangerous are not supported by the scientific literature. My goal here is to give you the nuance in plain language, show you the evidence, and give practical recommendations you can actually use in your kitchen and life.

What are seed oils and how are they made

When people say seed oils they usually mean vegetable oils extracted from seeds or grains such as canola, soybean, sunflower, corn, and sometimes sesame. These oils are high in polyunsaturated fatty acids, commonly abbreviated PUFA. The two important PUFA classes are omega-6 and omega-3. Many seed oils are richer in omega-6, but some, such as canola, have a notable omega-3 fraction as well.

There are two key points about how seed oils are produced that come up in debates: the method used to extract the oil and the subsequent refinement process. Most commercial seed oils undergo a high pressure and high temperature extraction and refinement process. That typically involves mechanical pressing followed by solvent extraction to recover more oil, and then degumming, neutralization, bleaching, and deodorization. Solvent extraction often uses a hydrocarbon solvent such as hexane to remove oil from the remaining pressed seed cake.

Critics worry about residual solvent, oxidation, and the possibility that high temperature processing creates unstable products that can promote oxidative stress when consumed. These concerns are not trivial, and they deserve attention. But they also need to be weighed against the totality of evidence from controlled trials and large epidemiological studies examining actual health outcomes. I address both the production concerns and the outcomes literature below.

Key differences between seed oils and animal fats

At the macronutrient level, the major difference is in fatty acid composition. Animal fats such as butter, lard, and beef tallow tend to be higher in saturated fatty acids and monounsaturated fatty acids, and lower in polyunsaturated fatty acids, compared to many seed oils. Olive oil is an important exception among plant oils because extra virgin olive oil is relatively high in monounsaturated fat, especially oleic acid, and also contains a rich profile of bioactive polyphenols.

Some high-level contrasts to keep in mind:

- Saturated fat: higher in animal fats, lower in most seed oils.

- Monounsaturated fat: high in olive oil and many animal fats; moderate in some seed oils.

- Polyunsaturated fat: higher in seed oils, especially omega-6 in soybean, corn, and sunflower oils. Canola oil is distinctive because it has appreciable omega-3.

- Bioactive compounds: extra virgin olive oil contains polyphenols and antioxidants that are largely absent in refined seed oils.

Those differences influence markers such as LDL cholesterol (why you shouldn’t worry too much about “bad cholesterol”), triglycerides, and inflammatory biomarkers. But it is crucial to interpret those markers in the context of hard outcomes such as heart attacks and mortality.

What the evidence actually says about health outcomes

One of the most illuminating points I emphasize is that when you directly compare seed oils to animal fats in randomized controlled trials and observational studies, the evidence does not support the alarmist narrative that seed oils are worse. In fact, many trials show that replacing saturated fats from butter, lard, or tallow with polyunsaturated fats from seed oils improves important cardiovascular risk markers and may reduce risk for hard cardiovascular outcomes.

Specifically:

- Randomized controlled trials comparing dietary patterns with higher polyunsaturated fats versus higher saturated fats have generally shown favorable effects on LDL cholesterol and sometimes reductions in cardiovascular events.

- Meta-analyses that aggregate trials comparing seed oils to animal fats tend to show that seed oils improve lipid profiles and do not increase mortality or cardiovascular events. In some cases, they reduce them.

- Across a spectrum of intermediate and hard endpoints, the balance of evidence favors replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat, at least in terms of lipids and coronary heart disease risk.

I want to be clear that this does not mean all seed oils are unconditionally superior to all animal fats in every context. Nutritional science rarely produces absolute statements that hold for every person and every circumstance. But the assertion that seed oils are inherently toxic or that they are demonstrably worse for cardiovascular and mortality outcomes is not supported by the majority of evidence.

Canola oil versus olive oil: a surprising comparison

One area that surprises many people is the direct head-to-head comparison between canola oil and olive oil. Many of us have been taught to revere extra virgin olive oil. I am a fan of extra virgin olive oil. I use it often, and its flavor and bioactive components make it a dietary staple in many healthy Mediterranean-style diets. Yet when you look at randomized studies and meta-analyses that directly compare canola oil to olive oil with respect to blood lipids, canola often performs very well, and in some analyses it reduces LDL cholesterol more than olive oil.

Why might that be? Canola oil has an unusual fatty acid profile among common vegetable oils. It contains a substantial proportion of monounsaturated fat and also has a higher omega-3 content than many other seed oils. While omega-6 is predominant in canola, the presence of alpha-linolenic acid, an omega-3 fatty acid, distinguishes it from many other seed oils that are nearly exclusively omega-6 heavy.

So the bottom line is this: if you are strictly looking at LDL reduction and triglyceride profiles, canola oil has shown favorable effects in randomized trials. That does not mean I will always recommend canola over olive oil from a culinary or holistic standpoint. Olive oil brings flavor and polyphenols that are associated with benefits in observational cohorts. But it is an important corrective to the narrative that seed oils are uniformly bad.

Processing concerns: hexane, heat, and oxidation

Processing matters. When people object to seed oils, their concerns often center on the refinement process: the use of solvents like hexane, the high heat applied during deodorization and neutralization, and the potential for oxidation products to form. These oxidation products, such as aldehydes and certain lipid oxidation byproducts, are biologically active and in theory could have negative health effects.

Here is how I break down the issue:

- Residual solvent: Most modern food-processing pipelines aim to reduce residual solvent to levels far below established safety thresholds. Several studies have measured trace hexane in edible oils and found concentrations well below regulatory safety limits. In some cases there were higher residues in olive oil compared to certain seed oils, but still below thresholds considered problematic.

- Oxidation: Polyunsaturated fats are more prone to oxidation than saturated fats. This is a chemical fact. The risk from oxidation is mostly relevant when oils are exposed to high heat, light, or oxygen, or if they are stored improperly and become rancid. Using oils within their expected shelf life, storing them away from light, and avoiding overheating them mitigates much of this risk.

- Refinement: Refined seed oils lose some natural antioxidants and may have a more neutral flavor. That is one reason people value extra virgin olive oil: it retains polyphenols and antioxidants that protect the oil and may contribute to health benefits when consumed raw or at low heat.

So while processing introduces theoretical risks, the real-world data comparing health outcomes between refined seed oils and animal fats do not show a clear advantage for animal fats. The theoretical chemical concerns need to be placed alongside outcome-driven evidence. That said, if you want to minimize potential exposure to oxidation products, choose oils appropriate for your cooking method, buy fresh, store them correctly, and do not repeatedly reuse oil for deep frying.

Why context and dietary patterns matter more than the oil itself

One of the most important points I stress is that oils rarely act in isolation. The dietary pattern that accompanies their use is a major determinant of health outcomes. When we demonize an ingredient in isolation, we often miss who typically consumes that ingredient and what else they are eating.

Consider the typical dietary patterns associated with heavy seed oil consumption in some populations. People consuming high amounts of seed oils often also consume large quantities of refined carbohydrates, processed foods, sugars, and calorie-dense, nutrient-poor meals. That combination creates a pro-inflammatory, hypercaloric environment that drives weight gain, insulin resistance, and cardiometabolic disease. The seed oil becomes a marker of an overall low-quality diet.

Conversely, people who use extra virgin olive oil daily are often those who assemble diets intentionally: fresh salads, whole grains such as sourdough bread, high-quality proteins, and less processed foods. Olive oil is a marker of a Mediterranean-style pattern that is associated with strong health outcomes.

That does not mean the oil is irrelevant. It matters. But the context is often the real driver. If you replace butter or lard in a diet of processed pastries with a refined seed oil but keep the pastries, sugar, and low-quality carbs constant, you might see an improvement in LDL but no major improvement in overall risk unless the rest of the pattern changes.

Economic and accessibility considerations

Finally, a practical reality: cost matters. Premium extra virgin olive oil, organic butter, and grass-fed products cost more than refined canola or soybean oil. For a family on a budget, the cheapest cooking fat that allows them to prepare filling meals matters. When advising people about diet, I always balance ideal recommendations with what is affordable and sustainable for the person.

If a family cannot afford to buy extra virgin olive oil by the liter and grass-fed butter every week, shifting to overall better choices that fit their budget is a better long-term strategy than pursuing a perfect oil profile that is not sustainable. This is one reason I emphasize context and overall dietary quality rather than declaring one source of fat categorically toxic.

Practical cooking recommendations

Here are simple, practical rules I follow and recommend. They are designed to minimize oxidation risks, preserve flavor, and fit a range of budgets.

- Use extra virgin olive oil for dressings, cold applications, and low to moderate heat cooking. It is my go-to because it tastes great and carries antioxidants. If you love the flavor, use it raw or gently warmed.

- Use refined oils with higher smoke points for high-heat applications. If you are deep frying occasionally or need a neutral oil for high-heat searing, refined canola or refined sunflower oil are acceptable choices. Avoid reusing frying oil repeatedly.

- Limit routine deep frying. Deep frying foods frequently contributes to a poor dietary pattern even if the oil itself is not inherently toxic.

- Store oils properly. Keep oils in a cool, dark place and avoid heat and light exposure. Small bottles are often better than giant containers if you do not use oil frequently.

- Smell and taste test. If an oil smells or tastes rancid, discard it. Rancidity is a sign of oxidation and indicates it is not suitable for consumption.

- Savor polyphenol-rich oils. Extra virgin olive oil and toasted sesame oil bring flavor and some protective antioxidants. Use them where they contribute to food enjoyment and overall diet quality.

Eating out strategies

Pro tip: When you’re dining at a restaurant and want to avoid seed oils, you can politely say that you’re “partially allergic” to them and request that your food be cooked in butter instead. Most restaurants will accommodate this kind of request without issue, and it’s an easy way to enjoy your meal without stressing about the cooking oil.

Supplements and vitamins: clear recommendations and exact dosages

Given the discussion about fatty acid profiles and oxidation, many people ask me what supplements to take if they regularly consume seed oils or want to optimize their fatty acid intake. Below I provide specific, evidence-informed supplement recommendations I use personally and recommend on BetterLife’s VIP protocol. These are general suggestions and do not replace medical advice. If you have specific medical conditions, are taking medications, are pregnant, or breastfeeding consult a qualified healthcare professional before starting any new supplement regimen.

1. Fish oil or marine omega-3 supplement

Rationale: Increasing the omega-3 content of your diet can help improve the omega-3 to omega-6 balance, lower triglycerides, support brain and cardiovascular health, and provide anti-inflammatory benefits. If you consume limited fatty fish, supplementation is the most reliable way to ensure adequate EPA and DHA.

- Recommended dose: 1,000 to 3,000 mg combined EPA plus DHA per day. Most commonly I recommend starting with 1,000 mg combined EPA plus DHA daily for general health and increasing to 2,000 to 3,000 mg per day if you have elevated triglycerides or cardiovascular risk factors, under medical supervision.

- Form: Triglyceride or re-esterified triglyceride forms are generally well absorbed. Ethyl ester forms can be effective if taken with a fatty meal.

- Timing: Take with a meal that contains fat to enhance absorption.

- Notes: If you are on blood thinning medications consult your clinician as high doses of omega-3 can have mild antiplatelet effects.

2. Vitamin E as an antioxidant

Rationale: Vitamin E is a fat-soluble antioxidant that protects cell membranes and may help reduce lipid oxidation. When PUFA intake is higher, the theoretical need for antioxidant protection increases.

- Recommended dose: For general maintenance I recommend meeting the RDA of 15 mg alpha-tocopherol per day, which is equivalent to roughly 22.4 IU of natural vitamin E. For individuals consciously increasing PUFA intake or who regularly consume higher amounts of seed oils I often recommend a modestly higher supplemental dose such as 30 to 60 mg alpha-tocopherol (approximately 45 to 90 IU of natural vitamin E) daily, but I do not routinely recommend doses above 100 IU without medical oversight.

- Form: Prefer mixed tocopherols that provide a spectrum of vitamin E forms rather than isolated alpha-tocopherol alone. Mixed tocopherol supplements often list the total mg and provide a favorable antioxidant profile.

- Notes: Vitamin E is fat soluble so take with a meal containing fat. Avoid very high doses long term without clinical supervision.

3. Vitamin C

Rationale: Vitamin C is a water-soluble antioxidant that works synergistically with vitamin E and contributes to the protection against oxidative stress. It helps regenerate oxidized vitamin E as well.

- Recommended dose: 500 to 1,000 mg daily is a reasonable range for most adults seeking antioxidant protection. I commonly recommend 500 mg with breakfast and consider an additional 500 mg with dinner if needs are higher.

- Notes: High doses of vitamin C are generally well tolerated, though doses above 2,000 mg per day can cause gastrointestinal upset in some people.

4. Multi-nutrient considerations: vitamin D and magnesium

Rationale: Vitamin D status (why you need more vitamin D) and magnesium (not all magnesium is the same) are foundational for metabolic health and can indirectly support cardiovascular and inflammatory profiles. While they do not specifically mitigate seed oil issues they are part of a sensible baseline nutrient strategy.

- Vitamin D: Check your serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D. For many adults I recommend 1,000 to 4,000 IU daily depending on baseline levels and sun exposure. Target a 25OHD level in the 30 to 60 ng/mL range. Dosages above 4,000 IU should be overseen by a clinician.

- Magnesium: 200 to 400 mg daily of elemental magnesium (magnesium citrate, glycinate, or malate forms) is a practical range to support sleep, metabolism, and general health.

5. Mixed tocopherols and polyphenol-rich supplements

Rationale: If your diet includes a higher proportion of PUFAs, supplementing with mixed tocopherols and consuming polyphenol-rich foods or concentrated extracts can provide additional antioxidant defense for lipids.

- Mixed tocopherols: look for a product that provides a mixture of alpha, beta, gamma, and delta tocopherols. Typical supplemental doses align with the vitamin E guidance above.

- Polyphenols: daily intake of polyphenol-rich foods such as berries, green tea, and dark chocolate is beneficial. Supplements such as standardized olive leaf extract or green tea extract can be used, but I prefer whole-food sources first.

These recommendations reflect a combination of available evidence and cautious, practical dosing that I use personally and recommend on Betterlife. They are designed to support fatty acid balance and reduce the theoretical oxidative burden that could arise from higher PUFA intake.

How I apply this in my kitchen and daily life

I want to be very explicit about what I do every day and why. Translating theory into practice is where most people get stuck, so here is the honest, practical approach I use and recommend:

- Extra virgin olive oil is my primary oil for dressings, finishing dishes, and low-heat cooking. I love its flavor and the additional polyphenols it provides. I usually purchase a reputable brand and keep it in a dark bottle in the pantry.

- For higher heat cooking such as stir frying or occasional deep frying I will use a refined oil with a higher smoke point. If cost is a concern for the household, refined canola is a pragmatic option. If flavor is central and budget allows, I use refined avocado or high-oleic sunflower oil for searing at high temperature.

- I rarely deep fry at home more than occasionally. When I do, I try not to reuse the oil many times and I cool it, filter it, and dispose of it properly after a couple of uses.

- I include fatty fish in my diet regularly and I take an omega-3 supplement of about 1,000 mg combined EPA and DHA on most days. If someone in the household has elevated triglycerides I raise that dose under medical guidance to 2,000 to 3,000 mg combined EPA plus DHA daily.

- I take a mixed tocopherol supplement providing around 30 mg alpha-tocopherol equivalent and eat vitamin C rich foods daily. I also make sure vitamin D and magnesium are adequate based on testing and symptoms.

- I focus on whole foods, vegetables, quality protein, and minimize refined carbohydrate and sugar intake. This is the primary driver of health outcomes in my view.

How to choose oils for different uses

Here is a simple table in list form to guide your selection. I present it as use cases rather than ranking oils from best to worst because context matters.

- Cold dressings and finishing oils: extra virgin olive oil, unrefined sesame oil for flavor

- Low to medium heat cooking: extra virgin olive oil, butter for flavor when appropriate

- High heat searing and frying: refined canola, refined avocado oil, refined high-oleic sunflower oil

- Deep frying: refined oils with high smoke points. Avoid frequent reuse.

- Baking: neutral refined oils when a neutral flavor is desired; butter or coconut oil when flavor and texture are prioritized

FAQ

Are seed oils the cause of modern chronic disease?

No. Seed oils are one possible contributing factor among many, but the modern rise in chronic metabolic disease is multifactorial. It includes excess calories, refined carbohydrate and sugar intake, sedentary lifestyle, sleep deprivation, stress, smoking, and environmental factors. Focusing solely on seed oils is unlikely to move the needle as much as addressing the overall dietary and lifestyle pattern.

Should I avoid seed oils completely?

No. I do not recommend complete avoidance for most people. Instead choose oils appropriate for the cooking task, prioritize whole foods, and emphasize dietary patterns rich in vegetables, quality protein, whole grains or minimally processed carbohydrates, and healthy fats. If budget allows I favor extra virgin olive oil for many uses. If budget limits you, refined canola or soybean oil are reasonable and evidence-based options.

Is canola oil worse than olive oil?

Not necessarily. In head-to-head trials looking at blood lipid outcomes, canola oil has performed very well and sometimes better than olive oil for lowering LDL. Olive oil brings polyphenols and a culinary advantage that often aligns with healthier overall dietary patterns. Both oils can be part of a healthy diet depending on context.

Should I take supplements if I eat seed oils?

Supplementation is not mandatory but can be helpful depending on your diet. A daily omega-3 supplement providing 1,000 mg combined EPA and DHA is a reasonable baseline for most adults who do not regularly eat fatty fish. I also recommend meeting vitamin E requirements and considering mixed tocopherols if your PUFA intake is high. Vitamin C, vitamin D, and magnesium are other sensible baseline nutrients to monitor and supplement as needed.

What about smoke points and oxidation?

Smoke points are a practical guide. Use oils with higher smoke points for high-temperature cooking and avoid overheating oils. Store oils away from heat and light, consume them before they go rancid, and avoid repeated reuse for deep frying.

Are there specific biomarkers I should monitor?

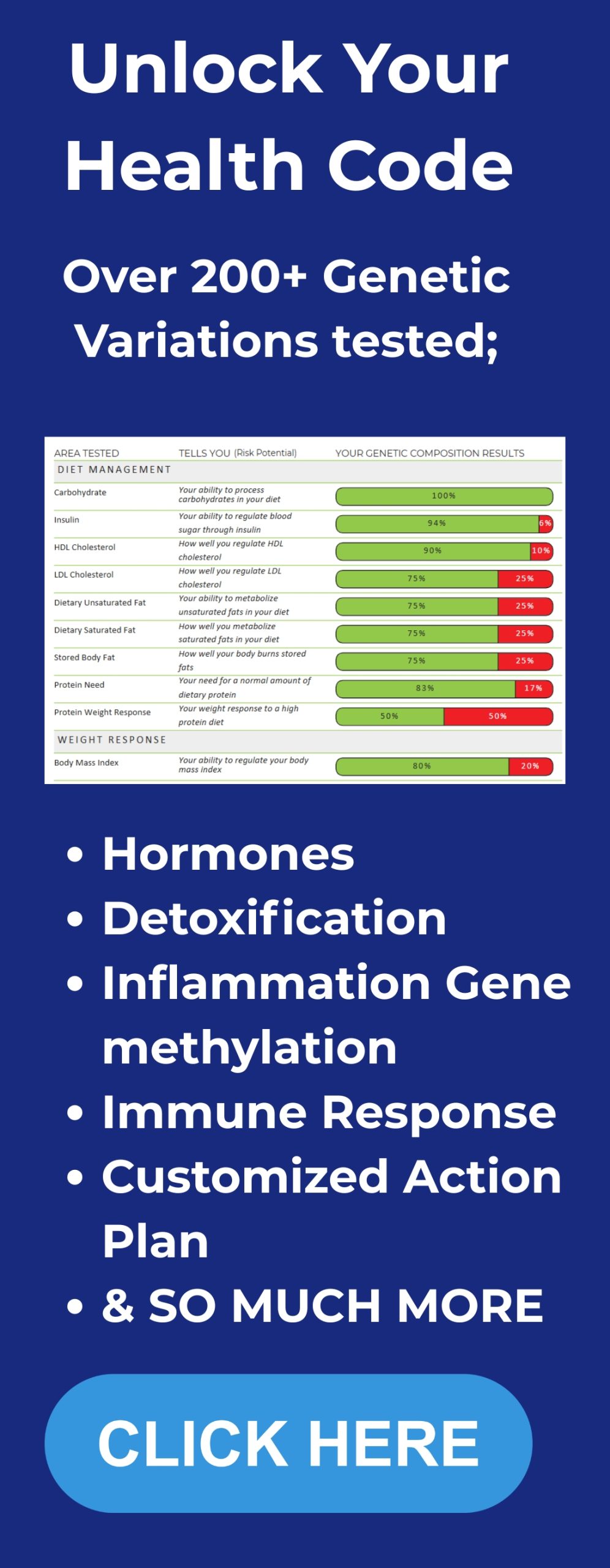

For most people, monitor the standard cardiovascular and metabolic markers such as a fasting lipid panel, HbA1c, fasting glucose or insulin, and inflammatory markers like hs-CRP if clinically indicated. If you increase omega-3 supplementation or are at cardiovascular risk, discuss lipid testing and medical monitoring with your clinician. If you want more tailored recommendations, you can also get personalized DNA insights to understand how your genes affect fat metabolism and nutrient needs.

How do I feed a family on a budget while avoiding seed oil paranoia?

Prioritize whole foods and minimize processed and sugary foods. Use a pragmatic oil strategy: extra virgin olive oil when possible for dressings and low-heat use, refined canola or sunflower for high-heat cooking when cost matters. The overall quality and balance of the diet are far more important than obsessing over a single ingredient.

Final thoughts

This debate is a classic example of how polarizing nutrition narratives can obscure nuanced evidence. Seed oils are not a simple single-character villain. They are part of a complex dietary landscape that includes processing, food choice, socioeconomic realities, and cultural patterns. I recommend a balanced, pragmatic approach that prioritizes food quality, appropriate cooking methods, and our Integrate protocols for personalized nutrition strategies when needed.