Today we’re diving into an important topic that often gets misunderstood: LDL cholesterol. You’ve probably heard it called the ‘bad cholesterol,’ but that label is misleading. LDL isn’t a burglar, it’s a bus. Its job is to transport cholesterol and triglycerides from your liver to tissues that rely on them. Far from being harmful, these molecules are vital building blocks. Cholesterol serves as the raw material for essential hormones like progesterone, estrogen, pregnenolone, and testosterone. When we reduce LDL to nothing more than a danger sign, we miss its crucial role in supporting balance and function throughout the body. In this post, we’ll break down the science of LDL, why it’s so important, and how understanding its true purpose can help you make smarter, more practical health decisions.

Table of Contents

- Why LDL gets a bad reputation

- LDL is a bus. Cholesterol is the cargo

- Metabolic health changes the LDL story

- Arteries not veins – a clue to mechanism

- Statins – how they work and why the decision is not always simple

- What lab tests do I recommend you ask for?

- Exactly what I recommend for supplements and dosages

- Dietary context matters – saturated fat versus polyunsaturated fat

- How to decide: lifestyle first, drugs when necessary

- What to say to your clinician in one or two sentences

- Practical, step-by-step action plan

- Frequently asked questions

- Final practical notes

- Closing and a reminder

Why LDL gets a bad reputation

In population studies, higher LDL often correlates with higher rates of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. That leads to the simple story many of us were taught: LDL rises, plaque builds, heart attacks increase. But correlation does not automatically mean causation, and LDL is always present in circulation. If you dig deeper into the data, the relationship between LDL and heart disease depends heavily on metabolic context. That is the critical nuance most clinicians and many guidelines ignore.

LDL is a bus. Cholesterol is the cargo

Think of LDL as a bus. The bus picks up cholesterol and triglycerides at the liver, a central depot, and drops them off in tissues that need those building blocks. LDL particles carry valuable passengers. The body needs cholesterol. We make it in the liver and elsewhere, and we also eat it. There are genetic conditions that make clear how essential cholesterol is: people with Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, where an enzyme in the cholesterol synthesis pathway is dysfunctional, suffer major developmental problems, susceptibility to infection, sleep issues, and high fetal mortality. One of the therapeutic approaches for those patients is a high-cholesterol diet because cholesterol is truly necessary for life and resilience.

In animal studies, lowering LDL excessively made animals more vulnerable to infections. Higher LDL in certain human cohorts associates with lower rates of hospitalization for infections, and in some older cohorts which is age 75 and up, people with higher LDL sometimes live longer. These are inconvenient facts if we insist LDL is an absolute evil. Instead, LDL’s risk appears to be context dependent, strongly modulated by metabolic health.

Metabolic health changes the LDL story

The most decisive variable that determines whether LDL is a marker of risk is insulin sensitivity. If you are metabolically healthy – that typically means normal fasting insulin, normal triglycerides, and higher HDL – LDL is a much poorer predictor of cardiovascular disease. If you are insulin resistant or diabetic – low HDL, high triglycerides, higher fasting insulin – LDL becomes a stronger marker and is much more likely to be associated with atherosclerotic disease.

To illustrate, imagine a Framingham-like dataset: take everyone’s LDL and plot it against cardiovascular events. In the whole group you might see a modest rise in risk with higher LDL. But split the cohort into subgroups by HDL – a practical proxy for insulin sensitivity – and the picture changes. Those with high HDL (say above 70 mg/dL) show almost no relationship between LDL and cardiovascular disease. Those with low HDL (below 25 mg/dL) show a steep relationship: higher LDL, higher risk. That tells us the physiologic context – insulin sensitivity – is a key determinant of whether LDL matters.

Practical takeaway

When a clinician sees a high LDL number and immediately prescribes a statin without exploring metabolic context, they are missing half the story. I will give you exact tests and a step-by-step to use later in this piece so you can have a better conversation with your clinician.

Arteries not veins - a clue to mechanism

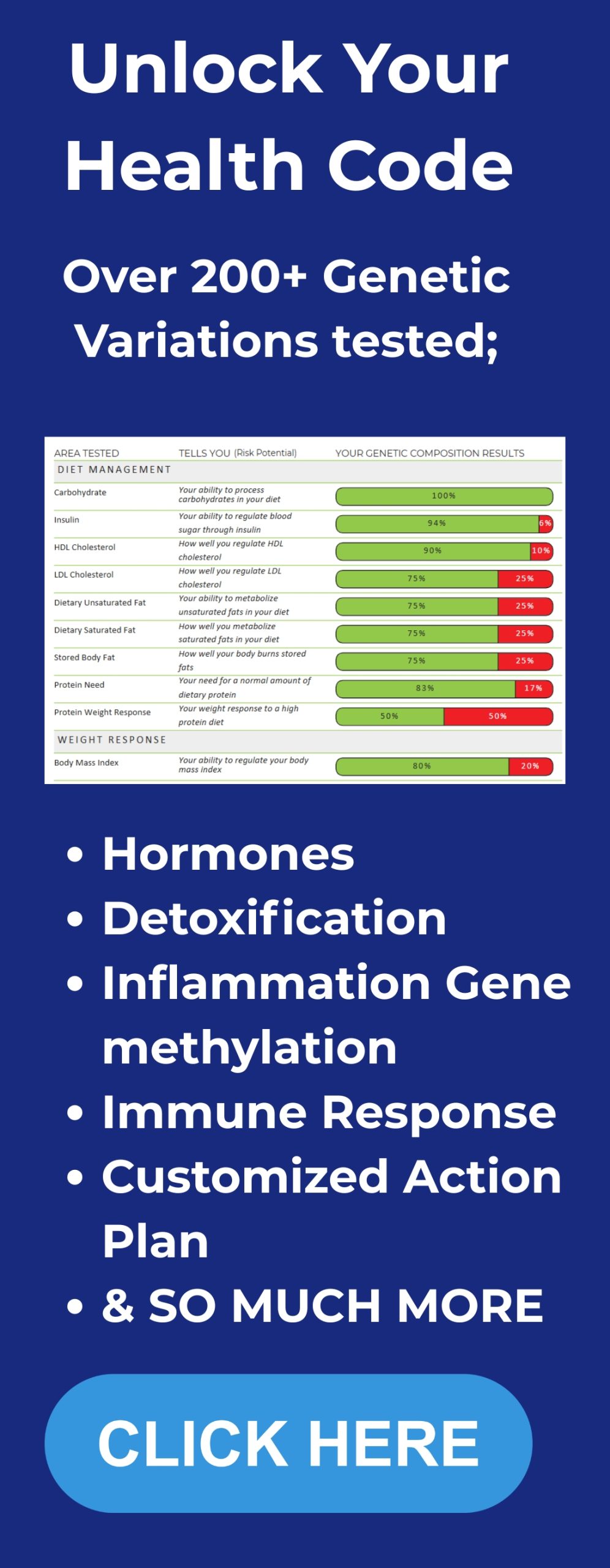

Here is a powerful thought experiment: if LDL particles themselves were inherently damaging the vessel wall and initiating plaque, why do we only develop atherosclerosis in arteries and not in veins? The same blood, with the same LDL, circulates through arteries and veins. Veins almost never develop atherosclerotic plaques in humans. The distinguishing feature of arteries is pressure and shear stress. Arteries are high-pressure, muscular vessels. That mechanical environment damages the endothelial lining more than the low-pressure veins. You need endothelial injury or dysfunction to initiate plaque formation. LDL may participate in or be trapped at sites of injury, but the initial trigger is damage to the endothelium. That damage is worse in people with impaired healing – notably those who are insulin resistant.

So the metaphor I use is this: are LDL and ApoB-containing particles the arsonists or the firefighters? In many cases they may be arriving as part of a repair process. In people with good metabolic health, the repair process is effective and doesn’t lead to progressive plaque. In those with metabolic dysfunction, the repair process is faulty and becomes a chronic, maladaptive sequence that results in plaque growth.

Statins - how they work and why the decision is not always simple

Statins inhibit HMG-CoA reductase, a key enzyme in the cholesterol synthesis pathway. That lowers cholesterol synthesis, reduces LDL production and increases LDL receptor expression in the liver, which lowers circulating LDL. Statins have been shown in randomized controlled trials to reduce cardiovascular events in secondary prevention – in people who already had a heart attack or established atherosclerotic disease. The benefit in primary prevention – giving statins to people who have never had a heart attack – is smaller and more contested.

Here is the clinical rub: blocking the cholesterol synthesis pathway doesn’t only reduce cholesterol. It also reduces synthesis of other biologically important molecules that share that pathway, including coenzyme Q10, squalene, and others. CoQ10 is an essential component of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Reduced synthesis can contribute to muscle aches, fatigue, and other symptoms that some people on statins report. Some clinicians prescribe CoQ10 supplementation to those who experience statin-associated muscle symptoms. A reasonable dosing approach is ubiquinol 100 to 200 mg per day or ubiquinone 100 to 200 mg per day with attention to formulation and absorption. That dose range is commonly used in clinical practice for statin-associated myopathy, but individual responses vary.

Important: If you are offered a statin, it is not an automatic wrong or right answer. It depends on your full risk profile, whether this is primary or secondary prevention, your metabolic status, and your values. But I think every clinician should contextualize LDL with insulin sensitivity and related markers before recommending lifelong therapy. And if you take a statin and develop symptoms, speak up and ask about CoQ10 and other supportive strategies.

What lab tests do I recommend you ask for?

When a clinician sees a single LDL value and says you need a statin, ask for context. Here is a practical panel I recommend to contextualize LDL and understand true cardiovascular risk:

- Fasting insulin – measured in micro units per milliliter (µU/mL). This is essential. Many doctors do not order it by default.

- Fasting glucose – to pair with insulin in the HOMA-IR calculation.

- HOMA-IR calculation – fasting insulin (µU/mL) x fasting glucose (mg/dL) / 405. A HOMA-IR under ~1.0 indicates excellent insulin sensitivity. Values above 2.5 suggest insulin resistance. These thresholds are approximate and labs vary.

- Fasting lipid panel – total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, triglycerides.

- ApoB – number of atherogenic particles. ApoB is useful, especially when triglycerides are high or LDL particle size is small.

- Lipoprotein little a – Lp(a) – a genetically determined risk factor that can independently raise risk. This is important because Lp(a) does not respond to diet or most statins. Because Lp(a) does not respond to diet or most statins, exploring your genetics can be useful. Consider our DNA Insights program for a deeper, personalized look at risk factors.

- Oxidized LDL (oxLDL) if available – a better predictor of cardiovascular events than LDL alone in many studies.

- hs-CRP – high sensitivity C-reactive protein – a nonspecific marker of inflammation. Elevated hs-CRP can identify higher risk independent of LDL.

- Advanced lipid testing or LDL particle number (LDL-P) via NMR if your clinician is willing. This gives particle counts rather than cholesterol mass.

When your clinician offers a statin simply because LDL is above an arbitrary threshold, you can say – politely and clearly – did you check my fasting insulin and HOMA-IR? Can we look at ApoB, Lp(a) and oxLDL? Those numbers will better tell us whether LDL is likely to be pathogenic in my case.

Exactly what I recommend for supplements and dosages

You will see lots of supplement protocols out there. I want to be specific because that is what people ask me for. Before I list doses I must state the obvious: this is educational and not individualized medical advice. Talk to a clinician you trust, and if you have medication interactions, prior conditions, or are pregnant or nursing, do not self-prescribe without supervision. Having said that, here are the supplements I often discuss with people who are thinking about LDL, statins, and metabolic health. These are evidence-forward doses commonly used in clinical practice.

- Coenzyme Q10 – ubiquinol 100 to 200 mg per day or ubiquinone 100 to 200 mg per day. If you are on a statin and develop myalgias, start at 100 mg daily and increase to 200 mg daily if needed. Ubiquinol is the reduced, more bioavailable form and may be preferable in older adults.

- Vitamin D3 – 2000 to 5000 IU per day depending on baseline level. Have your 25-hydroxyvitamin D measured and aim for a mid-normal range such as 40 to 60 ng/mL. Adjust dose based on labs.

- Magnesium – 200 to 400 mg elemental magnesium per day, often as magnesium glycinate or magnesium citrate for sleep and metabolic support. Many people are magnesium deficient which affects insulin sensitivity. You can find high-quality options such as CanPrev Magnesium inside our VIP product bundle.

- Omega-3 EPA and DHA – 1 to 3 grams combined EPA/DHA daily from high-quality fish oil or algae oil. For triglyceride lowering, 2 to 4 grams per day of EPA/DHA is commonly used clinically; for general cardiovascular support, 1 to 2 grams is reasonable.

- Vitamin K2 – MK-7 – 100 to 200 mcg daily. Vitamin K2 helps direct calcium to bones and away from arteries and has been associated with improved cardiovascular health in some studies.

- Berberine – 500 mg two to three times daily can reduce blood glucose and improve insulin sensitivity. This is often used as an alternative to metformin in people wanting a nutraceutical approach. Be mindful of interactions with other medications.

- Niacin – This raises HDL and can change LDL particle size, but at therapeutic doses (1 to 2 grams daily) niacin causes flushing and has safety concerns; do not take high-dose niacin without clinician guidance and monitoring of liver function.

- Antioxidants and polyphenols – green tea extract, curcumin, and resveratrol may reduce oxidative stress and oxLDL but dosing and formulations vary. Typical curcumin dosing is 500 to 1000 mg per day of a bioavailable extract; green tea catechins at 300 to 600 mg EGCG per day.

Why these? Because the worst things for LDL in terms of driving atherosclerosis are oxidation and chronic inflammation. If LDL is high but nonoxidized and you are metabolically healthy, your risk is much lower. Thus, strategies that reduce oxidative stress, improve insulin sensitivity, and support mitochondrial function make biological sense.

Dietary context matters - saturated fat versus polyunsaturated fat

You will often see two seemingly contradictory facts reported: eating saturated fat can raise LDL modestly; eating polyunsaturated vegetable oils can lower LDL but may raise oxidized LDL and Lp(a) in some contexts. Let us unpack that in simple terms so you can make targeted choices.

When people switch to a diet higher in saturated fat and lower in polyunsaturated fats, LDL may increase 10 to 20 percent in many people. That is a common observation. At the same time, oxidized LDL and Lp(a) often decline when saturated fat intake increases. Why? Because the outer phospholipid layer of LDL particles reflects the fatty acids we eat. If LDL picks up more polyunsaturated fatty acids on its surface, those fats are more fragile and susceptible to oxidation. Oxidized LDL is far more atherogenic than native LDL. So a program that lowers total LDL by increasing polyunsaturated fats may improve a numeric LDL but could increase the frailty of particles and the oxLDL burden.

This is consistent with the notion that LDL mass alone is a coarse marker. Oxidation status and particle number matter a lot. The homeoviscous adaptation model helps explain why cholesterol changes with dietary fats: cell membranes strive to maintain optimal fluidity. If you eat more saturated fat, membranes become more rigid and the body compensates by adjusting cholesterol in membranes and circulation. If you eat more polyunsaturated fat, membranes become more fluid and cholesterol may fall. Neither change is necessarily pathological by itself; the context and oxidation state matter.

How to decide: lifestyle first, drugs when necessary

For most people, the first and most powerful interventions are lifestyle oriented and targeted to improve insulin sensitivity:

- Improve dietary quality – reduce refined carbohydrates and sugars, prioritize whole foods, control portion sizes, and tailor saturated fat intake to personal response. If LDL rises on a higher saturated fat diet, do not panic. Check the context – fasting insulin, triglycerides, HDL, oxLDL, ApoB.

- Lose excess visceral fat – weight loss improves insulin sensitivity dramatically.

- Regular resistance and aerobic exercise – increases insulin sensitivity and improves HDL and triglyceride profiles.

- Improve sleep and reduce chronic stress – both worsen insulin resistance.

- Avoid smoking and reduce exposures to chronic inflammatory stimuli.

If after careful lifestyle optimization someone still has very high LDL and a high absolute risk – for example established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or multiple major risk factors – then statins or other lipid-lowering drugs like ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors may be appropriate. But that decision should be individualized and made after contextualizing metabolic health.

What to say to your clinician in one or two sentences

Many people feel flustered in clinic. If you want a short script to get the conversation started, try this:

“Can we evaluate my metabolic health before deciding on a statin? Please order fasting insulin and an advanced lipid panel including ApoB, Lp(a), and oxidized LDL if available.”

If your clinician looks blank when you say fasting insulin, be prepared to educate them briefly or ask for a consultation with someone who does this routinely. Too many clinicians focus on LDL alone because guidelines and liability concerns favor a straightforward approach. You can be part of the conversation and insist on context.

Practical, step-by-step action plan

If you or someone you care for has elevated LDL, here is a practical checklist I recommend following before reflexively committing to a lifelong statin.

- Repeat the fasting lipid panel to confirm persistent elevation. Make sure the blood draw is fasting.

- Order fasting insulin and fasting glucose and compute HOMA-IR. If HOMA-IR is high, prioritize insulin-sensitizing interventions first.

- Order ApoB and Lp(a). If ApoB is low relative to LDL-C, particle number may not be excessive. Elevated Lp(a) is a specific genetic risk factor and may indicate need for specialist consultation.

- Order oxLDL and/or LDL particle testing (LDL-P or NMR) if available. Elevated oxLDL is a more direct marker of oxidant-mediated risk.

- Assess inflammatory markers – hs-CRP, fasting insulin, hemoglobin A1c.

- Start a 12 week trial of lifestyle intervention oriented to improve insulin sensitivity: carbohydrate reduction focused on refined carbohydrates and sugars, consistent resistance training, 30 minutes of cardio most days, aim for 7 to 9 hours of sleep, and address stress. You can use our Integrate program to track labs, supplements, and progress step by step.

- After 12 weeks, recheck fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, lipids, ApoB, and oxLDL. If metabolic health has improved and ApoB/oxLDL remain low, the risk tied to LDL is likely much lower and a statin may not be necessary.

- If symptoms arise on any medication, discuss CoQ10 supplementation with your clinician and consider dose titration or switching statin types. Consider specialist consultation if Lp(a) is high or if you have strong family history.

Frequently asked questions

Isn’t LDL always bad?

No. LDL is a transport particle carrying cholesterol and triglycerides. It has essential physiological roles. Whether elevated LDL increases your cardiovascular risk depends strongly on metabolic health, inflammation, oxidative stress, ApoB particle number, and oxidized LDL. LDL in isolation is a limited marker.

What is the most important test doctors forget to order?

Fasting insulin. Many clinicians look only at fasting glucose or A1c and a lipid panel. Fasting insulin tells you about the metabolic milieu – whether tissues are insulin sensitive or resistant. Use fasting insulin with fasting glucose to compute HOMA-IR for better risk context.

Should I stop my statin if I feel fine?

Stop or continue medications only under clinician supervision. If you are on a statin and doing well without side effects and you have established cardiovascular disease or a clear benefit from the medication, continuation is reasonable. If you are on a statin purely for a marginal LDL elevation without contextual assessment, discuss a plan to measure fasting insulin, ApoB, Lp(a), oxLDL and to implement lifestyle strategies first. If you develop muscle symptoms, ask about CoQ10 and consider dose adjustments or alternative lipid-lowering strategies with your clinician.

What are reasonable CoQ10 doses for statin-associated muscle symptoms?

Common practice is ubiquinol 100 to 200 mg daily or ubiquinone 100 to 200 mg daily. Start at 100 mg and increase to 200 mg if symptoms persist. Ubiquinol may be better absorbed, especially in older adults.

What is oxidized LDL and why is it important?

Oxidized LDL refers to LDL particles whose phospholipid shell or components have been chemically altered by oxidative processes. Oxidized LDL is more atherogenic because it is taken up by macrophages via scavenger receptors, contributes to foam cell formation, and triggers inflammation. Diets high in fragile polyunsaturated fats can make LDL more vulnerable to oxidation unless protected by strong antioxidant defenses.

How do saturated fat and polyunsaturated fat affect LDL and risk?

Saturated fat often raises LDL modestly but can reduce oxLDL and Lp(a) in some contexts. Polyunsaturated fats tend to reduce LDL numbers but may make LDL particles more fragile and susceptible to oxidation, raising oxLDL in some situations. The net impact depends on overall diet quality, antioxidant intake, and metabolic health.

If my LDL is above guideline thresholds but my fasting insulin is low, should I start a statin?

Not necessarily. If you are metabolically healthy – normal fasting insulin, normal triglycerides, good HDL, low hs-CRP, low oxLDL and low ApoB – your short-term risk is likely lower. The decision should involve shared decision making with your clinician, factoring absolute cardiovascular risk, family history, and patient preferences. For many people in this context, lifestyle optimization plus close monitoring is a reasonable approach before initiating lifelong medication.

Final practical notes

If you are managing LDL on your own or helping someone else make sense of a lab result, remember these core priorities:

- Context matters. LDL alone is a poor screen without metabolic markers.

- Order fasting insulin and use HOMA-IR for a practical measure of insulin sensitivity.

- Consider ApoB, Lp(a), and oxLDL for a richer assessment of particle number and oxidation state.

- Lifestyle changes that improve insulin sensitivity can reduce risk dramatically and are reversible.

- If you take a statin and have symptoms, ask about CoQ10 100 to 200 mg daily and talk to your clinician about alternatives or dose changes.

- If you eat more saturated fat and your LDL rises modestly, that alone is not necessarily cause for alarm if your metabolic health is otherwise excellent. Check oxidized LDL and ApoB if you are uncertain.

For people who want a place to start, Betterlife contains resources and step-by-step guides that walk through testing, lifestyle protocols to improve insulin sensitivity, and evidence-based supplement recommendations including our full product collection designed to support metabolic health.. That site is a resource hub I’ve put together to help people have informed conversations with clinicians and to track objective improvements over time.

Closing and a reminder

Cholesterol is necessary for life. LDL is a vehicle for distributing essential lipids. The simplistic framing of LDL as universally bad leads to knee jerk prescribing and missed opportunities to address the true drivers of vascular risk. Insulin resistance, endothelial damage, inflammation, and oxidative stress – these are the processes I am most worried about. If you are insulin sensitive and metabolically healthy, I do not worry about LDL as much. If you are insulin resistant, get to work on reversing that problem first.

Remember to keep perspective, to ask for the right tests, and to work with clinicians who will contextualize lab results. If you already take a statin because of prior disease or high absolute risk, that is reasonable. If you are being told to take a statin solely because LDL is mildly elevated, ask for fasting insulin and ApoB before committing to lifelong therapy. And if you do take a statin and develop symptoms, discuss CoQ10 100 to 200 mg per day with your clinician as a reasonable starting approach.