Today we’re diving into one of the most misunderstood topics in health: cholesterol and heart disease. For decades, the conventional wisdom has painted cholesterol as the primary villain behind cardiovascular problems, but the latest evidence tells a very different story. By carefully looking at the science and clinical experience, a much clearer picture emerges of what truly drives atherosclerosis — and how to lower your risk the right way.

In this post, we’ll break down why the traditional cholesterol hypothesis doesn’t hold up, what’s really going on inside the arteries, and which diet, lifestyle strategies, and targeted supplements can make the biggest difference. Most importantly, we’ll show you the practical steps including the exact dosages we recommend to improve heart health and protect your longevity.

Table of Contents

- Overview: The central claim

- How the cholesterol hypothesis started and why it failed

- What actually causes atherosclerosis?

- Why polyunsaturated seed oils are not the answer

- The clinical evidence that questions statin-centric care

- My practical, evidence-informed plan to reduce heart disease risk

- Supplements I recommend and why: exact dosages and timing

- How I would approach a patient or reader with high LDL

- Common objections and clarifications

- Practical 30-day protocol you can follow

- What to expect and how to monitor progress

- Frequently asked questions

- Conclusion: Rethinking risk and putting metabolic health first

Overview: The central claim

The long-standing message most of us grew up with is simple: high cholesterol causes heart disease, so lower your cholesterol. For decades that message has driven public policy, medical practice and billions of dollars in drug sales. But the data and the historical record tell a different story. The original correlation evidence linking dietary fat, serum cholesterol and heart disease was flawed, and in some cases manipulated. Over time the policy response encouraged low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets and pushed polyunsaturated seed oils into the food supply. The result was not less heart disease. It was a large increase in cardiovascular disease, obesity and metabolic illnesses.

In place of the simplistic cholesterol-causes-heart-disease view, the evidence supports this alternative: atherosclerosis is an inflammatory, metabolic disease driven primarily by dysregulated carbohydrate and sugar metabolism, insulin resistance and glycation, with certain types of LDL particle changes and oxidative damage playing roles in plaque formation. Cholesterol itself is essential for life and is often protective, particularly in older adults.

How the cholesterol hypothesis started and why it failed

It is critical to understand the origin story. In the mid 20th century, investigators noticed correlations between dietary patterns, serum cholesterol levels and heart disease across populations. But correlation is not causation. The hypothesis hardened in the 1960s and 1970s into public policy recommendations that substantially reduced saturated fat and dietary cholesterol.

Two elements undermined the reliability of that story. First, several influential early studies and reviews were later revealed to be biased by industry funding and selective reporting. In particular, documentation shows that the sugar industry played a role in funding research and influencing scientific messages that shifted the blame to dietary fat and cholesterol instead of sugar. These kinds of undisclosed financial conflicts and selective publications biased the early narrative.

Second, large and rigorous subsequent studies and meta-analyses have failed to confirm a simple causal relationship between saturated fat, serum cholesterol and increased all cause mortality or cardiovascular mortality. In many analyses, either no association or an inverse association emerges. For example, meta-analyses and large population studies since 2015 show no consistent association between saturated fat intake and risk of heart disease or all cause death. In elderly populations, higher LDL has even been associated with lower mortality.

Key historical problems to note

- Selective use of data. Ancel Keys famously published the Seven Countries Study using a subset of available nations. When broader data were considered, the clear correlation he described disappeared.

- Unreported financial influence. Internal documents show the sugar industry funded research and public messaging that shifted attention away from sugar and toward fat.

- Misrepresentation of major cohort results. Reinterpretation of Framingham and other major datasets revealed claims in guidelines that misrepresented the original data.

The practical consequence was a global shift toward low-fat dietary recommendations and food manufacturing adjustments that promoted refined carbohydrates and industrial seed oils. The historical experiment that followed was to push billions of people toward higher carbohydrate consumption while lowering dietary cholesterol and saturated fat. That experiment produced rising rates of obesity, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease and cardiovascular disease — not the protection we expected.

What actually causes atherosclerosis?

Atherosclerosis is a complex, multi-step process. In my view, based on current evidence and clinical reasoning, the primary drivers are metabolic and inflammatory, not simple cholesterol load. The dominant mechanism I focus on is metabolic inflammation triggered by carbohydrate overload, insulin resistance and sugar-mediated damage to lipoproteins and vascular tissue.

Mechanistic summary

- High blood glucose and insulin resistance increase glycation and oxidative stress. Sugar molecules bind to proteins and lipids, a process called glycation or glycosylation, which impairs normal function.

- Fructose is particularly harmful. Fructose metabolism in the liver creates metabolites that resemble the damage seen from alcohol and promotes production of small dense LDL particles and triglyceride-rich particles.

- Small dense LDL particles and oxidized LDL are more atherogenic. When LDL particles become glycated or oxidized, their normal receptor-mediated clearance via hepatic APO B100 receptors is impaired. Macrophage scavenger receptors then uptake modified particles, forming foam cells and the fatty streaks that become plaques.

- Arterial wall damage and chronic inflammation allow these modified particles to be retained and accumulate into atherosclerotic plaques.

Modern reviews increasingly challenge the simplistic cholesterol-centric model of heart disease, highlighting metabolic and inflammatory pathways as more central to cardiovascular risk.

In short, sugar, refined carbohydrates, chronic high insulin and systemic inflammation set the stage. If the vessel wall is intact and oxidative/glycative stress is low, cholesterol in and of itself does not form plaques.

Why LDL number alone is not the full story

Serum LDL concentration is a crude marker. LDL particle number, LDL particle size, oxidation status and glycation status matter far more. Small dense LDL particles are associated with higher cardiovascular risk because they penetrate the arterial wall more readily and are more easily oxidized. But those small dense particles are driven by diets high in carbohydrates and fructose, inactivity and metabolic dysfunction. Treating LDL number in isolation without addressing underlying metabolic drivers misses the point.

Why polyunsaturated seed oils are not the answer

After policy shifted us away from saturated fat, the food industry replaced animal fats with vegetable seed oils high in polyunsaturated linoleic acid and omega 6 fatty acids. This seemed sensible because serum cholesterol numbers fell. But the clinical outcomes did not improve and in some analyses worsened.

Key points:

- Industrial seed oils are heavily processed and rich in omega 6 linoleic acid. These oils increase the omega 6 to omega 3 ratio and are pro-inflammatory in excess.

- The ratio between omega 6 and omega 3 matters. Omega 3 fats are anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective. Excess omega 6 competes for shared metabolic enzymes and lowers effective omega 3 function.

- Some randomized data show that replacing saturated fat with linoleic acid lowered LDL but increased cardiovascular mortality. This suggests LDL-lowering is not inherently protective if the replacement increases other risk pathways.

I recommend limiting industrial seed oils. Use natural fat sources such as butter, tallow, lard, coconut oil and extra virgin olive oil in moderation. Prioritize whole food sources of omega 3s such as fatty fish and consider supplementation when intake is inadequate.

The clinical evidence that questions statin-centric care

Statins are effective at lowering LDL levels. Yet the survival benefits in many populations are small, and statins have meaningful side effects. Several meta-analyses and large observational studies show modest gains in life expectancy only in selected high risk patients. In lower risk or elderly populations, benefits may be negligible and can be outweighed by adverse effects.

What the data show

- Large analyses show long term statin use in secondary prevention increases average survival by a few days to a few weeks, not years, in many cohorts. For primary prevention the benefit is smaller.

- Statins inhibit HMG-CoA reductase which reduces cholesterol synthesis but also reduces synthesis of coenzyme Q10. Loss of CoQ10 impairs mitochondrial function and can lead to muscle aches, weakness, and possibly cardiac muscle compromise when severe.

- In older individuals statin therapy often provides minimal net benefit and might be associated with harm in certain subgroups.

This does not mean statins have no role. For some patients at very high risk and with specific clinical profiles, statins are a valuable tool. However, I think they were adopted as a one-size-fits-all solution largely because of a mistaken premise about cholesterol. You must evaluate statin therapy in the context of total risk, expected benefit and side effect profile. When statins are used, I recommend co-supplementation with nutrients that protect mitochondrial function, which I detail below.

My practical, evidence-informed plan to reduce heart disease risk

Below is the protocol I recommend for most people seeking to reduce cardiovascular risk the right way. It focuses on fixing metabolic dysfunction, reducing inflammation and protecting cellular energetics rather than aiming at an arbitrary LDL target alone. Before making any change consult your doctor — especially if you are taking prescription medications or have existing medical conditions.

Diet: what to eat and what to avoid

- Avoid added sugars and refined carbohydrates. Eliminate sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit juices, sweets, desserts and most processed snack foods. Minimize starch-heavy foods such as bread, pastries, rice and pasta until metabolic health improves.

- Significantly reduce fructose. Fructose from table sugar and high fructose corn syrup is especially harmful for liver metabolism and small dense LDL formation. Keep total added fructose to a minimum.

- Favor whole foods and animal proteins if you tolerate them. Red meat, eggs, full fat dairy, organ meats and seafood are nutrient dense and provide cholesterol and fat-soluble nutrients your body needs.

- Use natural fats for cooking. Avoid industrial seed oils with high omega 6 content. Use butter, tallow, lard, coconut oil, ghee or extra virgin olive oil.

- Increase omega 3 intake from fatty fish (sardines, salmon, mackerel) at least 2 servings per week or use supplementation when necessary.

- If you prefer a structured approach, consider a low carb ketogenic or carnivore style approach for a period to reverse insulin resistance. Many people achieve rapid improvements in triglycerides, HDL, and small particle LDL profiles with carbohydrate restriction.

Lifestyle

- Exercise regularly. Resistance training and high intensity interval training improve insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular fitness.

- Prioritize sleep. Poor sleep increases insulin resistance and inflammation.

- Manage stress. Chronic stress drives inflammation; use techniques that work for you such as meditation, breathwork and social connection.

- Quit smoking and avoid air pollution when possible. Tobacco is a potent independent risk factor.

- Practice intermittent fasting if appropriate. Time restricted eating can improve insulin sensitivity for many people.

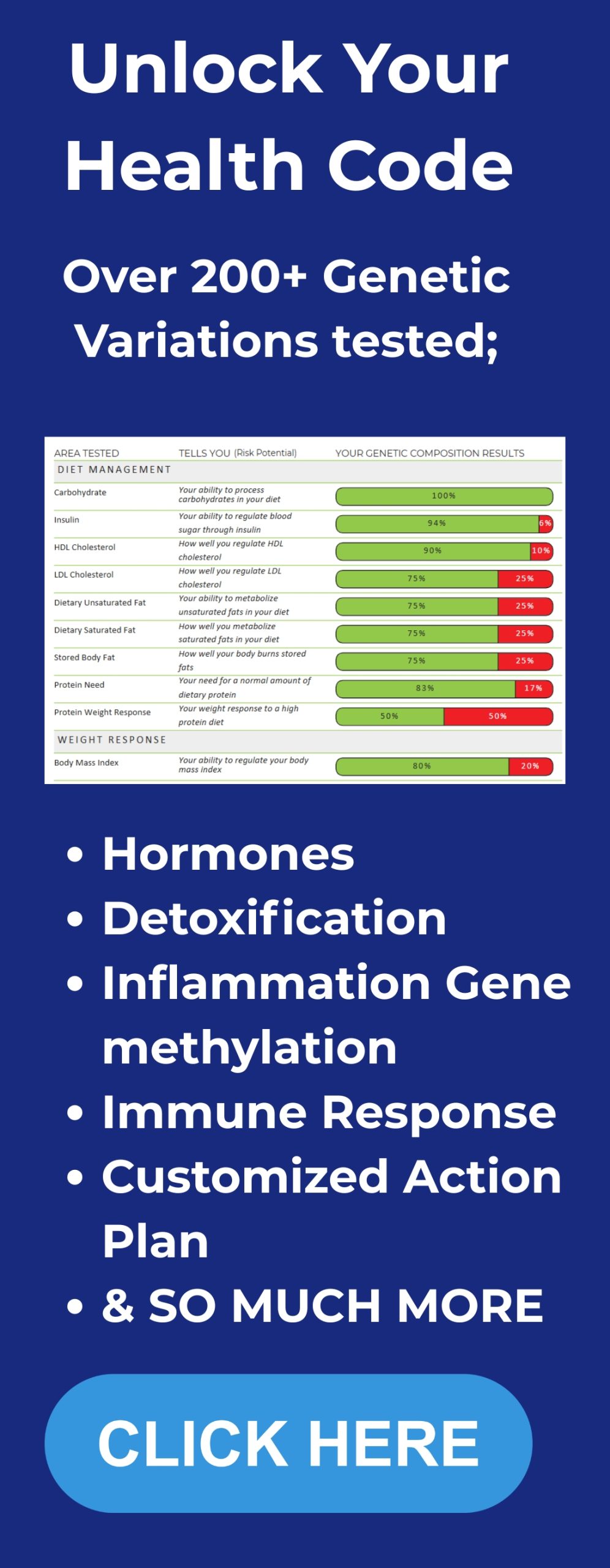

Targeted testing to move beyond total cholesterol

If you want to do this intelligently, get these tests rather than obsessing over total cholesterol alone:

- Advanced lipid panel with LDL particle number (LDL-P) and particle size or apolipoprotein B (ApoB).

- Fasting insulin, HbA1c, fasting glucose and fasting triglycerides to evaluate insulin resistance.

- High sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) as a marker of inflammation.

- Omega 3 index if available.

- Vitamin D 25 OH level.

- CoQ10 level if on long term statin therapy or experiencing muscle symptoms.

For a deeper layer of personalization, consider our DNA insights service which helps align lifestyle and supplement strategies with your unique genetics.

Supplements I recommend and why: exact dosages and timing

Below I list the supplements I commonly use and recommend as part of a heart-focused metabolic protocol. These doses are intended for adults without significant comorbidities and who are not pregnant or nursing. If you are on medications, especially blood thinners, or have kidney disease, consult your clinician before starting any new supplement.

Omega 3 fish oil (EPA and DHA)

Why: Omega 3 fatty acids reduce inflammation, lower triglycerides, improve endothelial function and reduce risk of sudden cardiac events. Several high quality trials and meta-analyses link higher omega 3 status to lower cardiac death.

Recommendation:

- Standard dose for general cardiometabolic support: 1,000 to 2,000 mg combined EPA and DHA daily.

- For elevated triglycerides or higher risk: 2,000 to 4,000 mg combined EPA and DHA daily, preferably under medical supervision.

- Choose a product that provides at least 500 mg EPA + DHA per capsule and is third party tested for purity and heavy metals.

Vitamin D3

Why: Low vitamin D is associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes, metabolic syndrome, and inflammation.

Recommendation:

- Typical maintenance: 2,000 to 5,000 IU vitamin D3 daily depending on baseline level. Aim for serum 25 OH vitamin D between 40 and 60 ng/mL (100 to 150 nmol/L).

- Test your level before high dose use and retest after 8 to 12 weeks of supplementation.

We recommend quality formulations such as CanPrev Vitamin D3 + K2 and Omega 3 available in our shop for reliable dosing.

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

Why: Statins reduce CoQ10 production. CoQ10 supports mitochondrial energy production in muscle and heart tissue and can reduce statin-related myalgias and protect muscle function.

Recommendation:

- If you are taking a statin: 100 to 300 mg CoQ10 daily in divided doses. A typical starting dose is 100 mg twice daily (200 mg total daily).

- If you are not on a statin but want mitochondrial support: 100 mg once daily is reasonable.

- Use ubiquinol form if you are older or have absorption concerns because it is more bioavailable, though ubiquinone at higher doses works as well.

Magnesium

Why: Magnesium supports vascular health, blood pressure control, glucose metabolism and ATP production.

Recommendation:

- Magnesium citrate, glycinate or taurate are well tolerated. Typical dose: 200 to 400 mg elemental magnesium daily, taken in the evening or split between morning and night.

- If you have loose stools, reduce dose or switch to glycinate/taurate.

Vitamin K2 (MK-7)

Why: Vitamin K2 helps direct calcium into bone and away from soft tissues including arterial walls. It supports vascular calcification prevention and works synergistically with vitamin D.

Recommendation:

- MK-7 form at 90 to 200 mcg daily. A practical maintenance dose is 100 mcg daily.

- Take with a fat-containing meal to improve absorption.

Berberine (for insulin resistance support)

Why: Berberine has glucose lowering and insulin sensitizing effects similar to metformin in some studies and can reduce triglycerides and improve metabolic parameters.

Recommendation:

- 500 mg twice daily with meals. Typical range 500 mg to 1,500 mg per day split throughout the day.

- Avoid if you are on medications that interact with CYP enzymes or have contraindications; check with your clinician.

Niacin (nicotinic acid)

Why: Niacin can raise HDL and modestly lower triglycerides and LDL. It can also improve lipoprotein particle profiles in some patients. However, it causes flushing and may have hepatic side effects at high doses.

Recommendation:

- Consider only under supervision. Typical effective dose: 500 to 1,000 mg nightly with aspirin 30 minutes prior to prevent flushing, if tolerated and safe for the person.

- Monitor liver enzymes if using above 1,000 mg/day or long term.

Vitamin C and polyphenol antioxidants

Why: Antioxidants reduce oxidative modification of lipoproteins and support vascular health.

Recommendation:

- Vitamin C 500 mg to 1,000 mg daily.

- Consider adding a polyphenol-rich extract such as green tea extract (EGCG 200 mg daily) or grape seed extract 100 to 200 mg daily.

Selenium and zinc

Why: Trace minerals support antioxidant enzyme function and immune resilience.

Recommendation:

- Selenium 50 to 100 mcg daily.

- Zinc 10 to 20 mg daily if you have low zinc status or increased needs. Avoid chronic high dose zinc without clinical indication.

Probiotics and gut health

Why: Gut microbiome influences inflammation and metabolic health. Dysbiosis can promote systemic inflammation.

Recommendation:

- Use a multi-strain probiotic with a total of at least 10 billion CFU daily, or consume fermented foods like yogurt, kefir and sauerkraut if tolerated.

How I would approach a patient or reader with high LDL

First, I would not reflexively treat a high LDL number alone. I would obtain a comprehensive evaluation including ApoB, LDL particle number, fasting insulin, triglycerides, hsCRP and assess lifestyle factors. The vast majority of cardiovascular risk in modern populations is driven by metabolic dysfunction. Therefore the primary approach is metabolic: dietary carbohydrate reduction, elimination of added sugars and fructose, weight loss when indicated, regular exercise and smoking cessation.

If the lipid particle pattern shows elevated ApoB or high LDL-P or an abundance of small dense LDL despite metabolic corrections, or if there is high baseline ASCVD risk, then pharmacologic therapy may be appropriate. When medications are used, I always pair them with the nutritional and lifestyle plan, and I co-prescribe mitochondrial supportive supplements such as CoQ10. I also monitor for statin side effects and reassess benefit periodically.

Common objections and clarifications

I am often asked whether cholesterol is harmful at very high levels, or whether my recommendations mean people should eat unlimited saturated fat. Here are answers to those practical concerns.

- Is very high LDL dangerous? Extremely high LDL levels driven by genetic familial hypercholesterolemia carry risk and warrant specialized evaluation and often pharmacologic treatment. My guidance is targeted at the general population with diet-induced cholesterol changes and metabolic syndrome, not classical homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia.

- Am I telling people to eat unlimited red meat? No. I recommend nutrient-dense whole foods including animal proteins for many people, especially those with metabolic disease. Quantity and context matter. If you eat a nutritionally complete, carbohydrate-restricted diet and your metabolic markers improve, that is the goal. Overeating any macronutrient to the point of weight gain is counterproductive.

- What about guidelines from major societies? Guidelines evolve. We have decades of accumulating evidence that complicates the simplified cholesterol narrative. I advocate for individualized care based on risk stratification and metabolic health rather than rigid adherence to LDL cutoffs alone.

Practical 30-day protocol you can follow

If you want to take a month to begin changing your risk profile, here is a focused, practical protocol designed to deliver rapid metabolic improvements while minimizing complexity.

- Eliminate added sugars entirely. No sugar sweetened beverages, desserts or candy.

- Reduce dietary carbohydrates to a level that improves energy and reduces blood glucose excursions. For most people this means < 50 to 100 grams of carbs daily; many will benefit from < 30 grams until blood sugars normalize.

- Eat protein at each meal: eggs, fish, beef, chicken, or other whole food proteins. Include a serving of fatty fish twice weekly.

- Use natural fats for cooking: butter, tallow, lard, coconut oil or olive oil. Avoid industrial seed oils.

- Start supplementation: Omega 3 fish oil 1,000 to 2,000 mg daily; Vitamin D3 2,000 to 5,000 IU daily; Magnesium 200 to 400 mg nightly; CoQ10 100 mg daily (200 mg if on statin); Vitamin K2 MK-7 100 mcg daily; Berberine 500 mg twice daily if you have insulin resistance. You can find these foundational products in our BetterLifeProtocols shop, bundled for convenience.

- Exercise five times per week combining resistance and aerobic work. Aim for 30 to 45 minutes per session.

- Sleep 7 to 9 hours nightly and practice stress reduction daily.

- Retest labs at 8 to 12 weeks: lipid panel, ApoB or LDL-P if available, fasting insulin, HbA1c, triglycerides, hsCRP, vitamin D, magnesium and CoQ10 as needed.

What to expect and how to monitor progress

Within two to twelve weeks you should see improvements in triglycerides, fasting glucose and potentially in HDL. LDL numbers may not behave the way you expect. In many patients LDL rises transiently when they shift to a lower carbohydrate diet because particle size and triglyceride content change. That is not necessarily harmful. What matters more is ApoB, LDL particle number and clinical risk.

If you see an unfavorable pattern such as persistently high ApoB and LDL-P after metabolic correction, discuss medication options with your clinician. If you start a statin, consider CoQ10 supplementation at 100 to 200 mg per day and monitor for muscle symptoms. Regular follow up and repeated testing is key.

Frequently asked questions

Q: Is dietary cholesterol a major cause of high blood cholesterol?

A: For most people dietary cholesterol has a modest effect on blood cholesterol. The body regulates endogenous synthesis. The major determinants of atherogenic lipid changes are carbohydrate-driven triglyceride metabolism and small dense LDL production associated with insulin resistance.

Q: Should everyone stop eating eggs and red meat?

A: No. Eggs and unprocessed red meat are nutrient-dense and provide essential nutrients. For people with metabolic syndrome, reducing carbohydrates and eating whole foods including animal proteins is often therapeutic.

Q: What about the omega 6 content of commonly consumed foods?

A: Modern diets have an extremely high omega 6 to omega 3 ratio due to seed oils and processed foods. Aim to reduce seed oil intake and increase omega 3 intake from fatty fish or supplements to bring the ratio closer to an anti-inflammatory balance.

Q: Are statins always bad?

A: No. Statins are appropriate and beneficial for many people with known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, very high LDL due to genetic causes, or certain high-risk profiles. The problem is treating LDL alone without addressing metabolic dysfunction and then assuming statins solve the underlying issue. If given, protect mitochondrial function with CoQ10 and monitor side effects.

Q: What is the single most important change someone can make?

A: Eliminate added sugar and dramatically reduce refined carbohydrates. For most people this single change improves insulin sensitivity, reduces triglycerides and shifts lipoprotein phenotype away from small dense LDL.

Q: Where can I find more resources and references?

A: I maintain a resource page on Betterlifeprotocols.com with references to the major studies, meta-analyses and clinical summaries that support this approach. You can also review meta-analyses published in major journals such as the BMJ and Journal of the American College of Cardiology for more context.

Conclusion: Rethinking risk and putting metabolic health first

The cholesterol narrative that dominated public health policy for decades was rooted in incomplete and in some cases biased early evidence. The real drivers of modern cardiovascular disease are metabolic dysfunction, inflammation, insulin resistance and the biochemical damage caused by excess sugar and processed carbohydrate. Cholesterol itself is essential and often protective. Blanket strategies that focus on lowering total cholesterol numbers without addressing metabolic health are misguided.

My practical approach is straightforward: reduce sugar and refined carbohydrates, avoid industrial seed oils, prioritize whole foods and omega 3s, exercise, sleep and manage stress. When indicated, use targeted supplementation to support mitochondrial function and reduce inflammation. Use advanced testing to guide decisions. Treat the patient in front of you, not a number on a form.

If you are ready to get started, consult us for detailed guides, meal plans, supplement checklists and tests that help you implement this program safely and effectively. Explore our Integrate program for structured coaching, or browse our products for vetted supplements and protocols.